Biosecurity in Aquaculture: Types of Pathogens and How They’re Treated

Pathogen… The word conjures up horrific thoughts of plague and death. It comes from the Greek word for ‘feeling’ or ‘disease’. It comes from kids with snotty noses that you pick up from daycare. They got it from some other kid whose parents aren’t as diligent about hygiene.

Simplistic maybe, but the principle is the same whether it is people or fish: pathogens are transferable and they get that way by making copies of themselves.

Download PDF Guide

No time to read this article now? We have a PDF version of this guide available for download. Just fill out the form and we’ll send it to you.

What are Pathogens?

Pathogens are organisms that cause disease. They can be viral, bacterial, fungal or parasitic. On the size scale, viruses can be nanometers wide (millionths of a millimeter) and only visible with an electron microscope, while bacteria are microns wide (thousandths of a millimeter) and visible with light microscopes at high power. Fungi and parasites are both macroscopic and microscopic. The common aspect among all of these pathogens is that when present in large enough numbers, they produce toxins, disrupt cell function, or overuse resources of the host while feeding their own needs to reproduce. Not a pleasant thought.

Viruses

Most viruses enter the fish by the mucosal linings of the gut or skin or by entering through gill tissue that has a thin cell membrane and a high surface area. In the gut, the virus must survive acid conditions and then enter surrounding tissues to become infectious. In the fish slime, it must survive wandering macrophages (scavenger white blood cells) and at the gill sites, it must pass unrecognized by other white blood cells. If all this is done, the virus can initiate infection.

Once inside the fish the virus must then enter a host cell that permits replication. This is done by commandeering the machinery for normal DNA replication and using it for its own evil Biosecurity purposes. After doing this, it makes several million copies of itself until the cell is full, bursts and spreads viral particles to other cells, either within the host or sometimes, outside the host.

The virus can relay its disease attribute by cell lysis (disintegration), producing a toxic substance, changing host cell function or inserting a bit of its genetic material into the cells genome. The most common observation is cell lysis as the virus multiplies in number.

Bacteria

Bacteria play the numbers game too. They enter the fish by the same methods or by open wounds suffered through trauma. Once inside, bacteria use the fishes’ plumbing system, find a tissue that it likes (specific or non-specific) and sets up shop. Here the buggers multiply rapidly. The disease aspect of the bacteria is directly by tissue damage or by production of toxins. These toxins may be a result of metabolism or as a mechanism to protect the process of replication. The latter is almost a defense mechanism at the bacterial level. Either way, having too many bad bugs share your body is not a good thing.

Fungi

Fungi, like some other pathogens, are opportunistic, and are sometimes secondary infections to other fish health issues. Fungi send out hyphae (filaments) to attach themselves to nonspecific tissue that may be vulnerable or susceptible. From there they multiply spreading throughout the tissue utilizing the host’s valuable energy resources.

Parasites

Parasites may use fish as an intermediary or primary host. As an intermediate host, the fishes’ chances of overt disease signs are small. However, as a primary host, the fish is the environment the parasite has been living for. Parasites don’t generally kill the host, but they tend to alter behavior and growth. The idea of having a macroscopic bug thriving to reproduce in you is not a pleasant one and it is easy to understand why the fish looks sick.

Antibiotics

Got an infection? Take a pill. But how does medication kill bugs? Antibiotics – those chemicals that kill bacteria – are also called antimicrobials and are of two general types: bacteriostatic and bactericidal. Bacteriostatics prevent the bacteria from multiplying by inhibiting cell division. The fish then has time to develop an immune response and finishes off the resident bugs using its own defense system. Bactericidal medications kill the bacteria outright (how?). Anti-fungicides have similar effects on fungi by either inhibiting growth or by making changes to the cell wall and membrane of the fungus’ hyphae. Poking holes in the cells of fungi causes’ salt and ion penetration that kills the cell and hopefully the fungus.

Parasiticides

Parasiticides are usually specific in toxicity to the target organism. The real challenge here is to kill the invader while keeping the host intact. These compounds usually focus on some particular feature of the parasites’ anatomy or biology and exploit that weakness.

On the good side, pathogens don’t normally live long outside a host. This is because they are dependent on a host for most of the necessities of life. Some may aestivate (go dormant) as spores or such, but generally they die. This is also the time to disinfect.

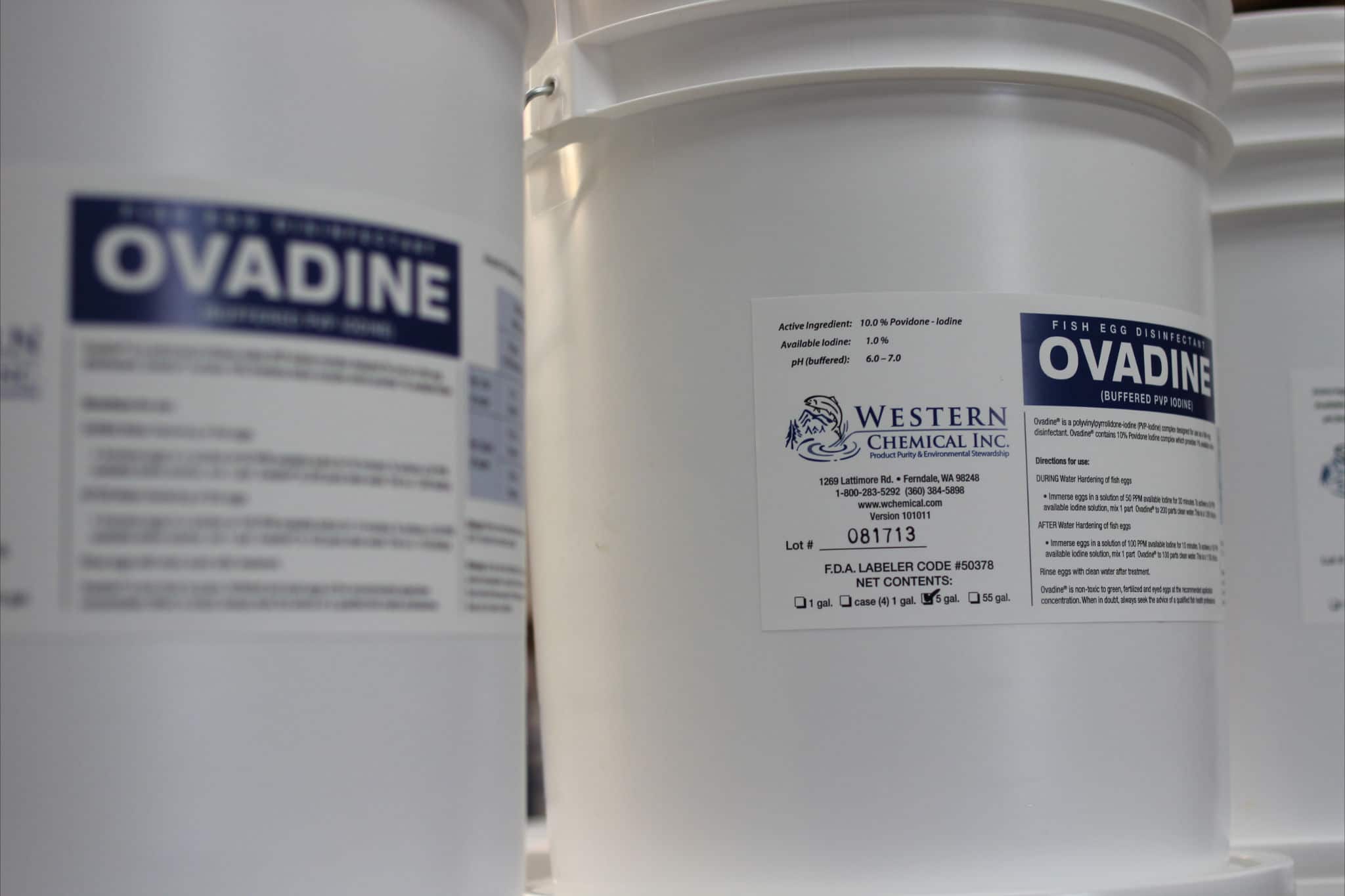

If the pathogen is outside the fish, it’s much easier to kill it. Not only is the environment bad for the pathogen, there are also more tools that can be used to kill it. Selective toxicity is not necessary because you have isolated the pathogen and do not have to worry about the host. This is the principle of disinfection.

A good disinfectant will kill the pathogen and prevent growth of new pathogens. Of course, in a hatchery or farm situation, the disinfection process must be safe for humans, fish and the receiving environment, otherwise some really nasty stuff could be used. Such uses would be irresponsible. The idea is to have a disinfectant that works with the efficiency of nuclear warfare, but without the aftermath. Biosecurity on fish farms has always been a challenge but there is no better time to kill a pathogen then when it is exposed, vulnerable and in search of a host.